Growing Knowledge as Play

Using a Zettelkasten to grow knowledge ambiently and playfully

Badminton is hard. It is fun, but my habits from playing tennis are translating into mistakes on the badminton court. It is frustrating and fun trying to get rid of those, and in any case it is good exercise.

But I do not go to the courts because it is exercise, even though it is. Nor do I go because it helps me get closer to my friends or because it passes the time. It is play, which is done for its own sake.

Play might be defined as any activity that, being done for its own sake, involves the expression of the player(s). Play is not even done for the sake of fun—it just happens to be fun.

Activities where you partake for the sake of some emotional stimulus, and, perhaps also themselves, include watching TV, scrolling through social media. These are not play. And what I find most distinctive between those activities and play is expression. Watching TV is an act of passive consumption, wheras playing badminton involves developing character and actively creating a personal style of play.

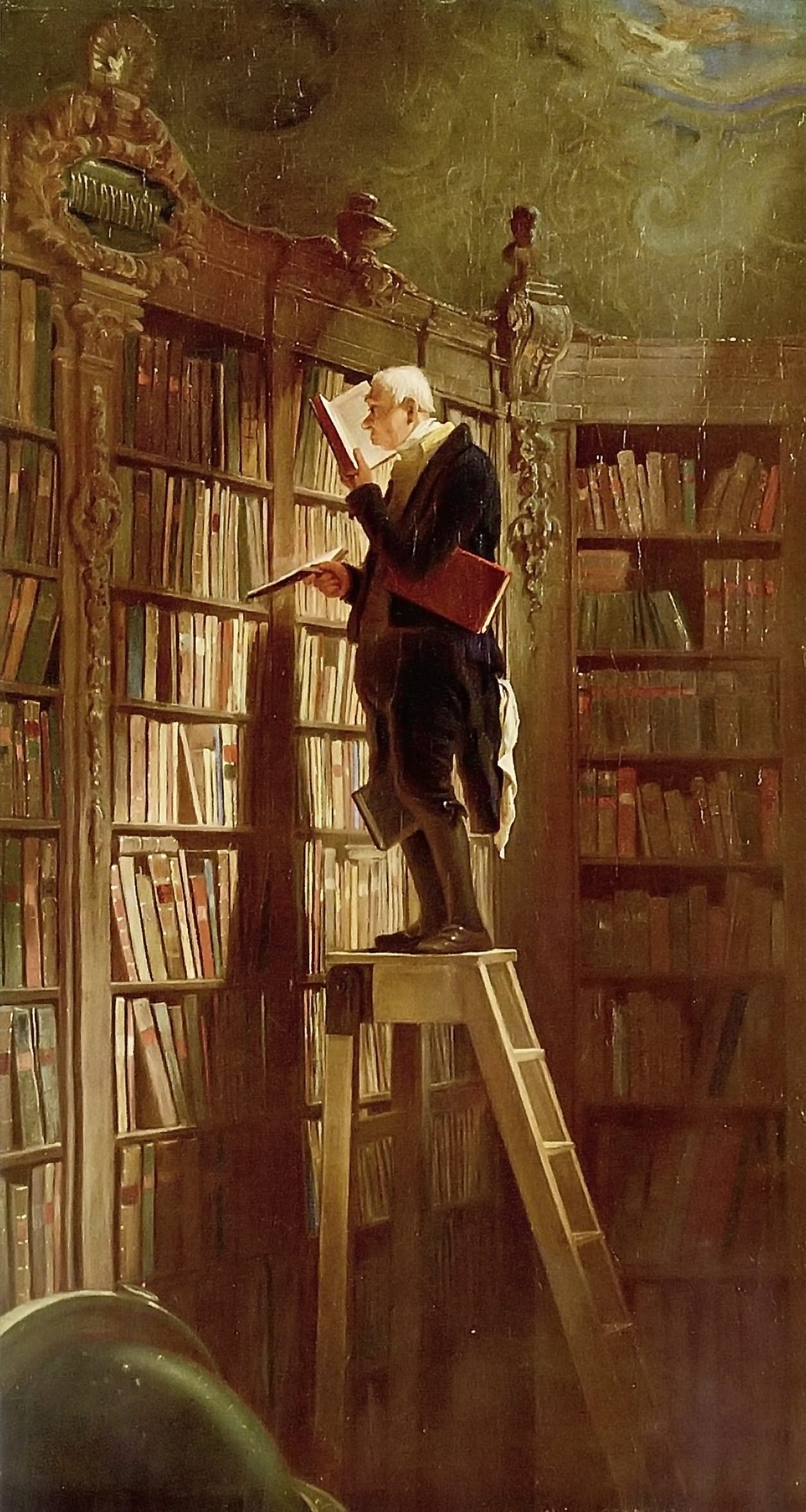

Another form of play I partake in is growing knowledge. Among my fellow aspiring intellectuals, research and writing are often seen as tasks, even if enjoyable. I see it as a fundamentally different activity.

And this approach has important consequences on people who do not work directly with knowledge, opening possibilities for more people. See, you may think of my knowledge growth as a luxury I am particularly fortunate to afford, but I disagree.1 In reality, the affordable form of growing knowledge is when it is play.

Interestingly, the key to all of this is not very difficult to understand or put into practice—the key is the Zettelkasten.

Accessibly Growing Knowledge

Some people in the world are fortunate enough to be able to devote most of their time to growing their knowledge. They read and write books and papers, attend conferences to listen to and give talks.

Most people are not like them. But the difference those fortunate few and the majority is not capability or interest, but simply the ability to devote time. That affordability is often one of circumstance and luck, which is very unfortunate—I believe that growing knowledge should be a possibility for everybody, not just those with ample time to do so.

Furthermore, the traditional conception of growing knowledge involves sitting down at a desk for an extended period of time, writing, reading pondering. Sometimes, it is going down to a lab to conduct some heavy-duty experiments. This is simply not possible for most people.

Thankfully, for those who cannot afford to devote such lengths of time or such mental energy, the traditional picture can be set aside. The alternative uses the Zettelkasten emphasizing its ability to grow knowledge ambiently.

Ambient Knowledge Growth

Taking notes without a Zettelkasten, you might have different notebooks for different projects, or maybe different school subjects. To grow knowledge, you write in these notebooks and read from them afterwards. Some sections of a notebook might become blog posts, and others might be practice for intense conversations.

But this requires some time to sit, study, and write. Many people never look back through their notes, and as a result their knowledge does not grow. And for this approach to taking notes, projects are crucial—without a project in mind, all the notes would be rigidly classified, unable to cross-polinate. You could not know which projects you might have in the future would benefit from some knowledge you' have picked up!

The Zettelkasten structure, by making all the knowledge immanent, places the emphasis not on projects but on the pieces of knowledge and their connections.

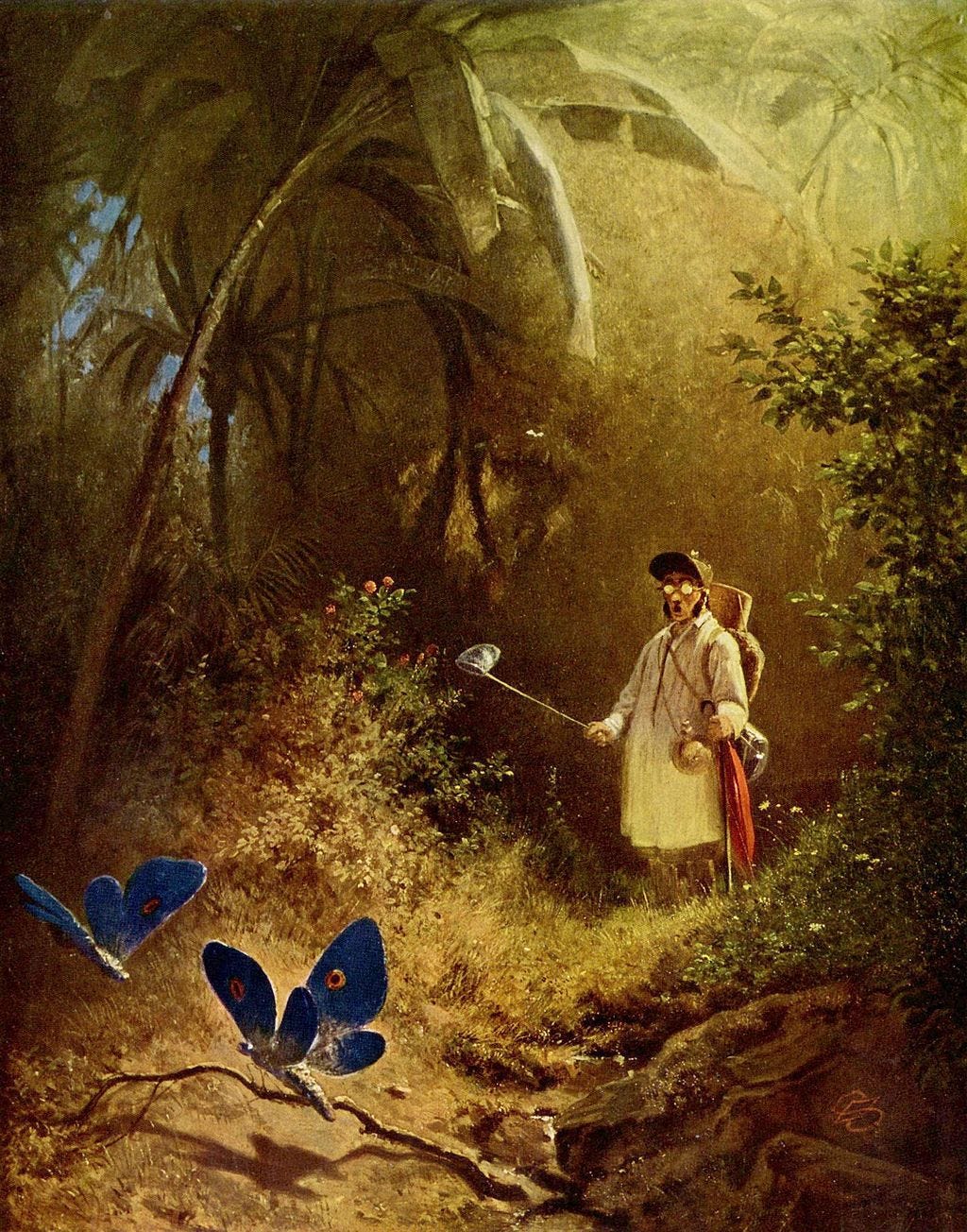

You can simply collect information you find interesting and make connections with other pieces of information. Notice that any information you find interesting has vast potential of future connections—you are not limited by the scope of a project. Instead, over time, scoped groups of connections appear organically that can be converted into fully-formed projects.

Also, with this approach, even if you work from within a project, the insights can be taken out of context and into other contexts, other projects, so that research for any project is research done for any number of any other potential projects.

In other words, the work you do is not merely directed towards individual projects, but rather ambiently growing knowledge from which multiple projects can emerge.

Ambience and Accessibility

This property of ambience also results in a greater accessibility.

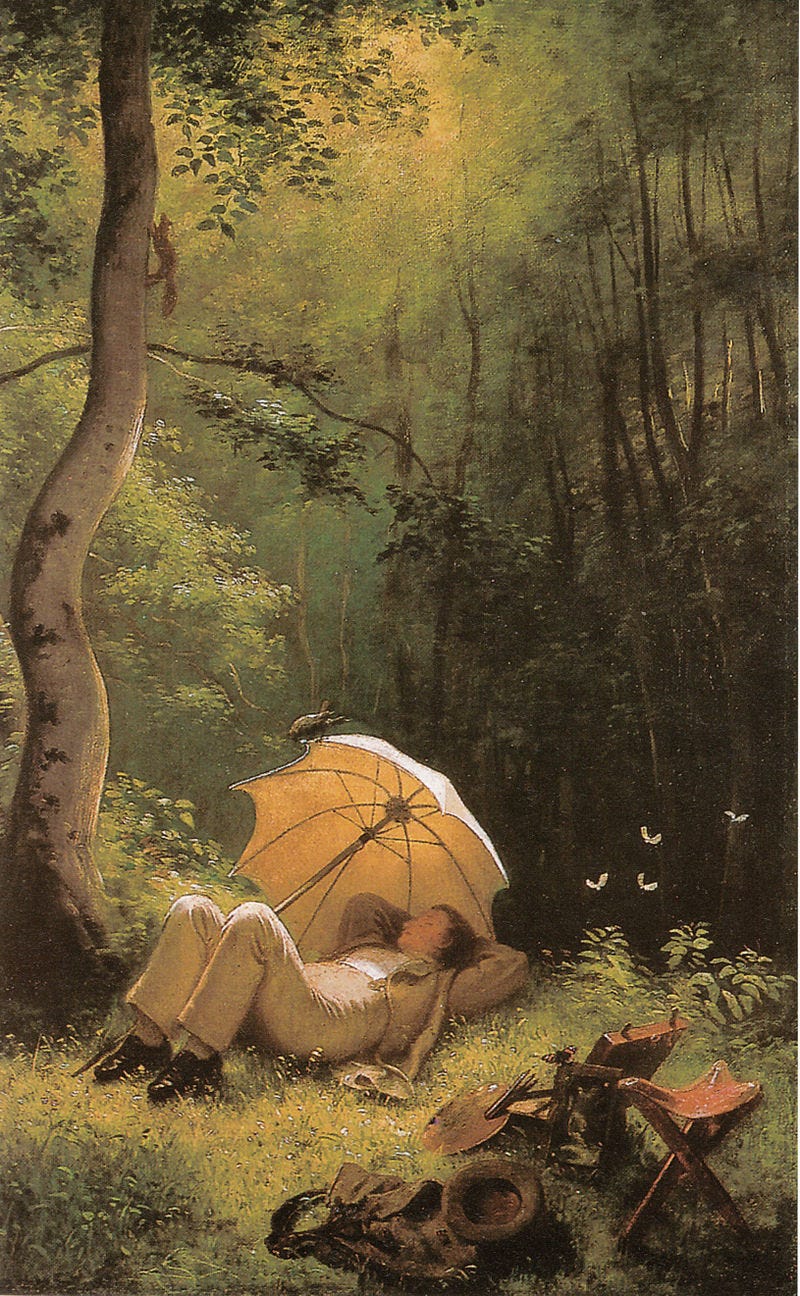

Since your efforts grow the garden ambiently, you do not have to work in the context of strict broundaries. You do not have to sit and stomach an entire book over months, eventually forgetting much of the context of a project. Instead, you can pick up what is interesting, and save it as an investment into a future connection.

If you have 15 minutes to spare, you could read a few pages of a book and take some short notes. Sometime in the future, you might look at those notes and make connections with some others. You might use your notes you put together a short paragraph about a subject. A few more of those, and you could have an essay published.

That is at the core of how I work with my Zettelkasten: When something feels right to dig into, when it is interesting or convenient, I can make valuable connections and grow my knowledge. It seems awfully playful, and that is because it is!

Playfully Growing Knowledge

For an activity to be play, according to my definition earlier, it must be done for its own sake. When working with projects in mind, research is done with the research question in mind—a sake other than itself. But in the Zettelkasten, where research can be done ambiently, sources are explored and connections are made on the basis of themselves being interesting—their own sake.

Another required aspect of play, as I mentioned, is expression. It is not difficult to realize how expressive and personal note making is. Note making is about incorporating yourself, since every connection you make is a result of your entire life.

Growing your knowledge does not have to be some elusive activity that could only be possible in another life. It is something you can grow slowly, ambiently, and in the time between your larger commitments. While growing in this way, you engage in a profound act of personal expression, and find an extremely rewarding mode of play.

Resources

There are more thoughts on ambient knowledge growth from Andy Matuschak’s ‘Executable strategy for writing’ note, under the name ‘undirected’. I highly recommend his notes for deep practical and theoretical insights into knowledge growth.

Some of my thoughts on the accessibility that Zettelkasten provides come from the so-so book Digital Zettelkasten Principles, Methods, & Examples and the fantastic book Where Good Ideas Come From. Where Good Ideas Come From is an amazing source to begin taking notes on, since it details creativity, problem solving, science, and much more.

There are more resources on getting started with Zettelkasten on my introductory post.

I recognize that I am awefully fortunate, especially in the sense that I can devote more time to this play.