Shuzan's Shippé

How will you answer Shuzan's question?

Shuzan held up his shippé, and said, “You monks! If you call this a shippé you omit its reality. If you don’t call it a shippé, you go against the factuality. Tell me, all of you, what will you call it?”

首山和尚,拈竹篦示衆云,汝等諸人,若喚作竹篦則觸,不喚作 竹篦則背. 汝等諸人,且道喚作甚麽.

So goes the 43rd case of the Mumonkan,1 a 13th century collection of Zen koans compiled by and commentaries written by a monk by the name of Mumon. I use the case as a tool in arguing for the following: Philosophy, defined loosely as any inquiry into singular, foundational truth, is misguided. Not only is such a singular foundational truth incoherent, it can also be a harmful heuristic that obscures insight instead of revealing it.

This essay was written for a class on Current Continental Philosophy. That class was my target audience, so I will now provide a few words to aid the reader without experience in academic philosophy: I develop a view throughout the essay I call “phenomenological pragmatism.” Phenomenology, as I use the term, has to do with focusing on what is experienced, as opposed to focusing on what is theorized. Pragmatism refers to my focus on ‘meaning’ rather than ‘truth.’ Thus, my view can be described as “focusing on the meaning of things experienced.”

If you find this essay interesting, or if you cannot make heads-or-tails of it, please stick around—I will write more about these concepts in more detail, in a more accessible way, and in a more social way. Consider subscribing so that you get notified when I publish those!

Back to the essay…

The word shippé,2 the way we use words together, and really the vast majority of the language we use, is not completely under our control. Jacques Derrida describes this condition in his “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences” as a state “of being implicated in the game, of being caught by the game, of being as it were from the very beginning at stake in the game.”3 Mumon describes these stakes in his commentary on the koan, proclaiming that “lifting up the bamboo staff is an order giving life or taking it away.”4 It is not just spoken and written language, but the ways in which the world operates that are out of our control. Our life and death literally depend on the ‘rules’ of the world, and Derrida is right to say that this makes us anxious.5 From this anxiety, we try to make as much sense of the world as we can with what we have.6 This sense-making gives us respite and is most comforting when asserted as certain, foundational truth.

Philosophy traditionally involves that same sense-making, that search for certain, foundational truths, that search for foundational reality. Unfortunately, something is amiss. Derrida points out that philosophy is conducted through language, which is to say through signifiers. Signifiers, for Derrida, are all that are needed for language. The meaning of signifiers does not come from signs, which involve some intrinsic relation with a signified, as had been previous thought by structuralists following Ferdinand de Saussure.7 After showing the sign to be incoherent, Derrida demonstrates that “the absence of the transcendental signified extends the domain and the interplay of signification ad infinitum”.8 The signifier “shippé” is not intrinsically linked somehow to some signified shippé of Shuzan. Instead, the meaning is a complicated network of presence and absence. Particularly, the meaning of every signifier is constituted by its complement.9

Given this, truth, reality, and Being, are constituted by their complements: non-truth, non-reality, and non-Being. But then in what sense, if they have more foundational parts, are these concepts of truth, reality, and Being, foundational? “The paradox,” Derrida expressed in the context of signs, was that “the metaphysical reduction of the sign needed the opposition it was reducing.”10 Philosophy then seeks foundational reality but will never be able to reach it since there is no single foundational signifier. This insight “undercuts the project of philosophical foundationalism, the project of building a final and unsurpassable foundation for thought.”11

Furthermore, reality is not the reality we think it is. More accurately, more perplexingly, reality is the reality we think it is, but it is only that, not something else. It is just what we think it is—our stories of it. But that makes it somehow not that reality, perhaps out there, that we think it is. For example, what could you say in consideration of your phone? What can you say about it that is not your interpretation? Nothing, since anything you could say has to be said, and said by you. Your phone is nothing but what you think of it. You could resist this notion by appealing to some phone ‘out there,’ separate from you, and asserting that it has some relation to you that grants it the status of being yours. In that case, you could insist that your phone really does exist in a manner separate from you. Even if you are correct and there is such a phone, any way you conceptualize it would be through your interpretations, simply because it is you who is doing so. But in the end, even that abstract phone and its mysterious relation to you could not exist purely on its own, since the terms used in proposing such a situation are linked to your language, to your other interpretations. The signifiers ‘phone,’ ‘relation,’ and even ‘you’ are all given meaning through your own network of signifiers. Your phone is your interpretation, or as Nietzsche put it, “there are no facts, only interpretations.”12

This is how we ‘omit reality’ when calling Shuzan’s shippé a “shippé.” But it’s also missing the point to avoid calling it a shippé altogether… and what a predicament you would be in if you couldn’t call a shippé a shippé! It’s evidently useful.

If the traditional concepts of foundational truth and of foundational philosophy are no longer tenable, what can replace them? As an example, what happens to statements like “the mind is completely mental,” as is sometimes claimed by philosophers of mind? What replaces such statements are methods that avoid letting such statements become totalizing, which would have them take on some foundational role. The techniques to prevent this come from two sources, one pragmatist and one pluralist. The pragmatist technique is to push further into the meaning of the statement in situations, so that it becomes meaningful in a network of meaning.13 The fact that the mind is mental, for example, might play an important part in an argument. The pluralist technique is to avoid being limited by this single interpretation, and instead be open to statements like “the mind is partially physical.”14 The result of this approach is a kind of pluralist pragmatism, where multiple interpretations are employed in different scenarios where they might fit best. If phenomenology is about focusing on ‘the things themselves’, this pragmatism is about focusing on ‘the interpretations themselves.’ If an interpretation is a ‘thing,’ then this approach may be called phenomenological pragmatism.

Indeed, pragmatic approaches are good alternatives when foundationalist truth is incoherent. But even if it were coherent, phenomenological pragmatism as an approach brings about more insight. A simple example from high school chemistry is the use of the Bohr model in teaching about the atom. Scientific consensus is that the Bohr model is overly simplified and does not hold truth. Yet, it is a source of insight into learning more about the atom, one that is still used today, even compared to models that might be ‘more true.’

The example provided, however, only demonstrates that foundational truth is not necessary for insightful models. To show that foundational truth would actually harm the picture consider the most accurate model of the atom taught in high school:15 the quantum model. By ‘accurate’ here I mean the least error-prone as is understood within the bounds of science.

Using this model might lead to better results than using the Bohr model, since it is more accurate. Unfortunately, this benefit comes at the cost of there being fewer opportunities to use the model in the first place: the Bohr model makes many meaningful claims, more than the quantum model does. It thus has more chances at being shown wrong—but that itself is an insight!

Another sense in which phenomenological pragmatism reveals more than foundational truth is in the ways interpretations interact with each other. Somebody in the latter camp may make a claim like “physicalism is true,” whereas the pragmatist, who cannot make such a strong truth claim, might say “physicalism is the only theory that accounts for the correspondence between brain and mind states.” If these sentences were answers to somebody’s question about physicalism, the pragmatist’s answer is clearly more informative, more insightful.

In some sense, it doesn’t really matter that I’m not being ‘completely truthful’ or ‘omitting reality’ when calling the shippé “a shippé” since it helps me talk about it.

Destabilizing a singular truth of the matter seems awfully relativist, doesn’t it? Anything could be true, so I can go around saying anything I want, without regard to what others say. But that anything can be true or not is not important to phenomenological pragmatism, since truth itself is not what is important. Truth is not on its own meaningful. Furthermore, proofs, which illustrate the components of an interpretation, become more important since understanding interpretations pragmatically puts the emphasis not on the ‘accuracy’ of the interpretation, but on the interplay of the interpretation with other interpretations, like highlighting where exactly there are contradictions and keeping them in mind.

When somebody makes a claim, a relativist might be forced to accept it, but a phenomenological pragmatist can ask “why,” and “what do you mean,” and have reasoned arguments. On the flip side, the approach somehow makes other non-traditional modes of doing philosophy, like poetry, music, and visual arts, more legitimate and important. Propositional statements, since they are all about asserting truth, become ever so slightly less superior over forms that express less assertive notions, since interpretation and meaning becomes important.

The pluralistic and pragmatic answer to Shuzan is to call the shippé “a shippé” when it seems suitable, and not call it “a shippé” when that seems suitable. I will not miss the reality, but nor will I miss the factuality. That might not seem very philosophically sophisticated, but there is a reason why this Koan is part of a highly respected text in Zen traditions, traditions sought after by practically minded people, and enticing to high-minded academics. One of the biggest insults philosophers can give each other is a simple “oh, that’s interesting,” or “that sounds about right.” This Koan serves as a reminder that good philosophy has staying power, disturbs us, and changes our sense of meaning, if not our lives. “The soul becomes dyed with the color of its thoughts,” says Marcus Aurelius.16 Let us do philosophy that benefits our souls.

Blyth, Reginald Horace. MUMONKAN—The Zen Masterpiece. 2002nd ed., The Hokuseido Press, 1966.

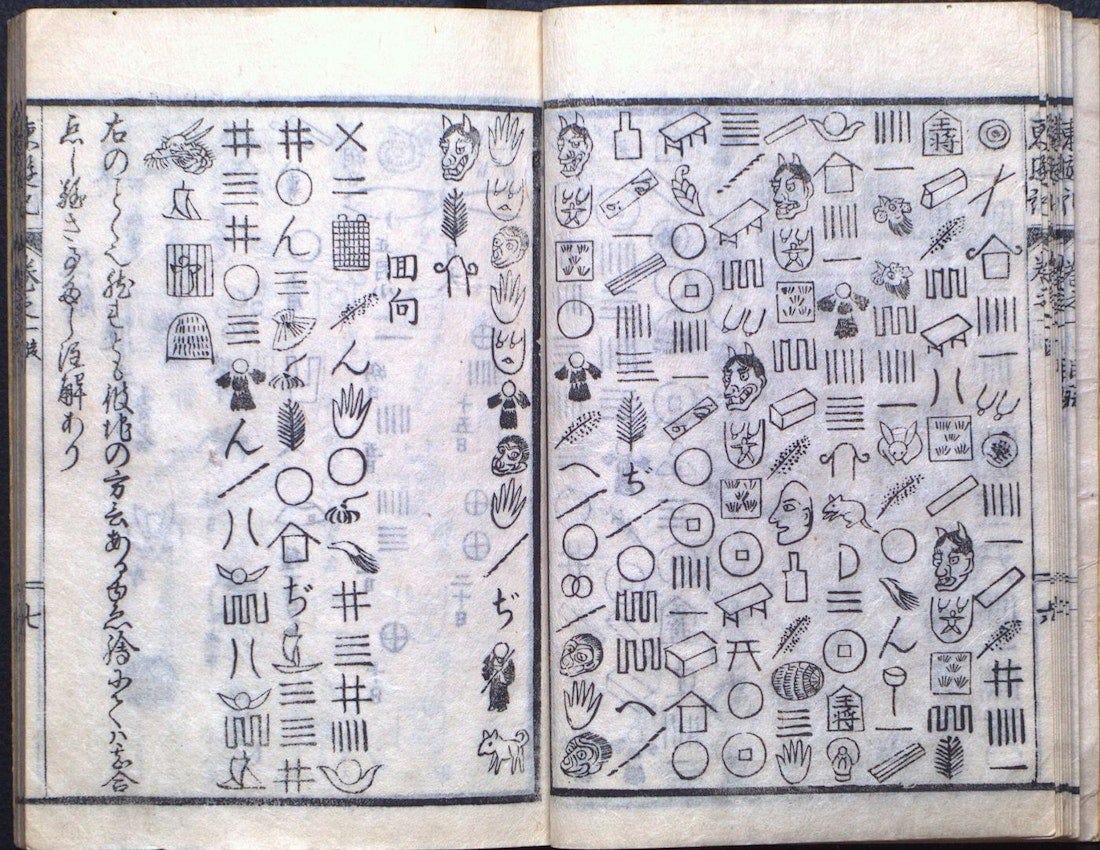

A shippé, for which another name is “broken-bow,” 破弓, because it is the shape of one, is a piece of bamboo about three feet long with wistaria bound round the head of it. Originally it was used as an instrument of punishment, and then an insignia of authority by masters and priests. (Blyth, 279-80)

Derrida, Jacques. “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences.” The Structuralist Controversy, edited by Richard Macksey and Eugenio Donato, The John Hopkins University Press, 1977, pp. 247–72.

This quote on page 248.

MUMONKAN, p. 282

Derrida, p. 248

Derrida, p. 248

For more on signs, signifiers, and even signifieds, consider reading this synopsis on Ferdinand de Saussure’s wikipedia page.

Derrida, p. 249

May, Todd. Gilles Deleuze: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Todd May’s clear explanation of Derrida can be found early in the first chapter. This sentence references page 11.

Derrida, p. 251

May, p. 12

Found on the IEP’s article on Gianni Vattimo

Read more in my essay Mind as a Figment of Yours

Once again, more in Mind as a Figment of Yours

This might be the most accurate model that has scientific consensus, even outside of school, but I am not completely certain.

This is not exactly how the phrase has been translated in editions I have found, which usually omit the ‘color.’ The phrase is found in the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, section 5.16.